the weight of the thing in your hand

This is a special edition. Last night at Granola, I ran an event Thom Wolf [cofounder + chief science officer of Hugging Face] and Sélim Benayat [AI products and design lead of Nothing] to go deep building next-gen hardware. We had intense interest for the event and I promised some of the five hundred signups we couldn’t make room for (not a typo; five hundred) I’d do a write-up. Luckily Granola is pretty great at taking notes. This is long and deep on community flywheels, how hardware is hard and not and the future of form factors — hope you enjoy it as much as I did.

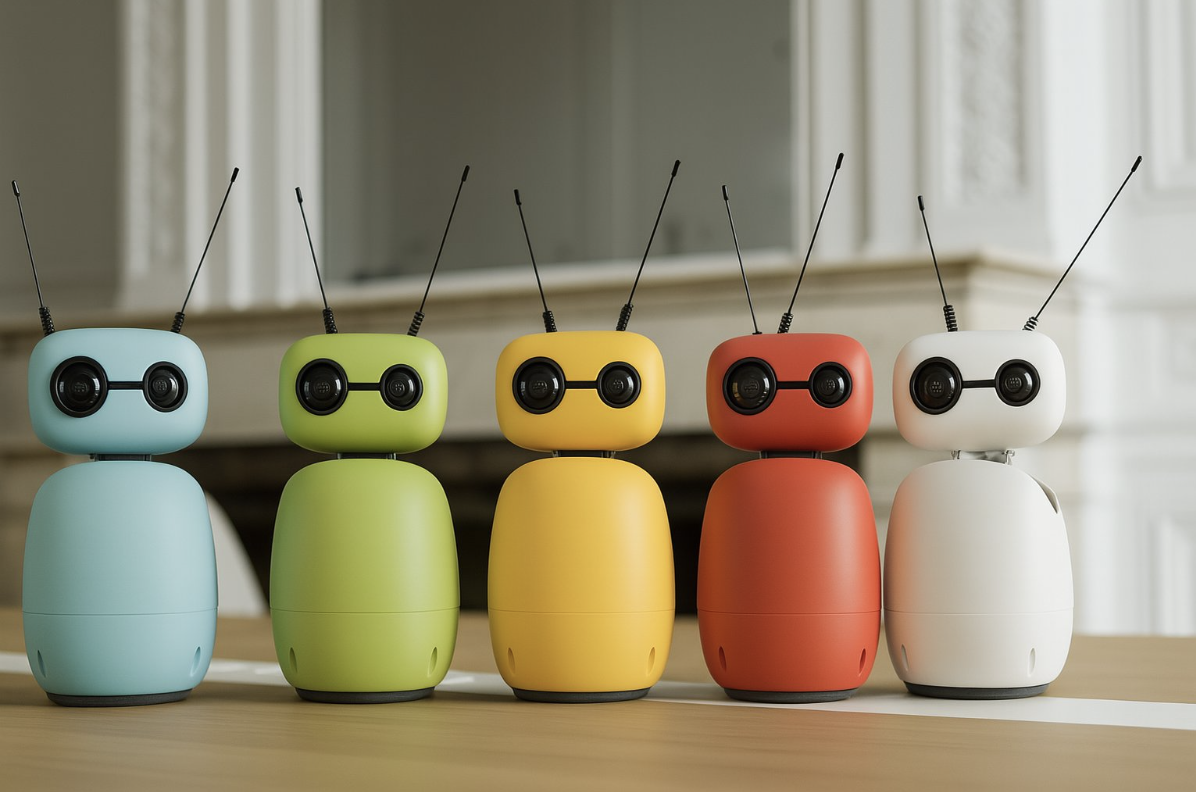

[At one point Nothing's design lead told me he liked my trousers which made my year] Sarah: Thom, how did the Reachy project start within Hugging Face? Thom: So I’d met these guys building Pollen Robotics through our open source robotics libraries. They were based near us in France so we began to speak and when I visited them, they had a piece of hardware on their desk that reminded me of the Pixar lamp — small and white. Eventually the alignment became clear, we acquired Pollen and began thinking through colloborations. So many robot demos we see are these dark dystopian things; we want to make something open source, affordable, playful, something my kids would love. As we discussed this, I remembered the Pixar lamp and we said “let’s make a robot like the lamp”. We announced it a few months ago and we were delighted with the response. We’ve got a million dollars worth of orders already. Sarah: There are some clear choices you made in building Reachy— from the price to the launch video which centres very different use cases to what we normally see robots do — how did that come about? Thom: It happens that the product lead for Richie Mini is a woman, Charlotte. She’s amazing. Before doing product, she was training as an actress; so she likes to play. The woman we see cooking in the video is actually the product lead for Reachy. Sélim: That’s cool. Thom: We basically had two days to make the video. Our head of Frankfurt has a daughter, who is six, who is the daughter you see in the video. I messaged an old friend from university who lives there; you have a son, do you want to be in the video? Everything came together. For the direction, the idea was let’s try to convey sunny human interactions with the robot. It’s never humans alone with the robot; in many cases the human is interacting with our humans and the robot is a medium. Like when you play with your child, you have a game and you’re both playing. You both move pieces on the game; you’re not alone with the game. That’s the idea we have for each mini and what we wanted to show. Sarah: What do you think are misconceptions in how AI is integrated into physical robotics and hardware? Thom: To be honest, I don’t think there’s a lot of cases right now where AI is really integrated. But we have to build and that means we can decide how we want to build. Not in a scary way; maybe we want it to be open source, collaborative, you can program it easily with your son or daughter. I like the idea of using AI to reinvent hardware and breaking walls to making this more beautiful future I want to live in. Press enter or click to view image in full size Sarah: I love that. On beauty — Sélim, Nothing has always been known for transparency and raw design. How do you think about translating that philosophy or sensibility into the work you’re now leading? Sélim: The angle we’re taking is to be even more radically transparent, because I think AI can be scary if it just does things without informing you. You need to be kept in the loop. The experiments and the products that we’re currently shipping have a lot to do with showing what’s happening behind the scenes. Giving the user the ability to edit or remove and try to understand why the AI did something. As an example, one of the newest OS launches that we did is you’re going to be notified as soon as AI starts working in the background; you’ll see a little banner to tell you what model and what’s happening. From a design perspective, transparency, privacy, and security is at the forefront when we take decisions. Sarah: Something you said to me when we caught up last time that I thought was really interesting was around timelines. You know, we think of hardware as being a thing that gets improved and shipped every couple of years, and we think of software as being more iterative. How do you think about that given how much AI has accelerated and automated that iteration? Sélim: I joined to build a software company inside of Nothing. If you know Nothing, you might know us for excellence in hardware manufacturing and hardware design. We started with earbuds then a phone. In startup land, Nothing is only four and a half to five years old. You keep on doing what makes you win until you don’t win anymore with that strategy. Before I joined, the team doubled down on manufacturing and design excellence that had been build up, which meant the entire DNA of the company was geared towards hardware cycles. The industrial team has a certain timeline they work with; anything that’s shipped over to Shenzen to be manufactured has to pass certain tests. You measure 100 times and cut once. The entire company centres around that. Carl started to think about bringing more of a software culture to London; software designers bring a different rhythm and cadence to the work. I started in hardware then spent ten years in pure software so bring a cadence of fast shipping and being close to the end user. The key to success in software is to listen to what the user really wants. With software, it’s easy. You launch it on Twitter and then you just look at the replies. Sarah: It certainly worked for Bento. Sélim: Yes. There, the playbook was launch on social and listen to feedback. Screenshot replies into Slack and reality check ourselves. Sarah: So Nothing is historically a hardware-first company bringing in more of a software culture. Hugging Face is an AI software company doing hardware. This is why I thought this duo on the panel was interesting. How have the company cultures evolved as the scope has grown? Thom: We all think the grass is greener! For us, going from software to hardware, we had to be realistic that we were learning things and it was a different world. As Selim said, you’re used to the fast iteration cycles and shipping things that don’t yet work perfectly. Hardware is different. You cannot ship a robot that has a lot of problems. It’s one reason we acquired Pollen as we needed experts. Hardware has this very nice thing — and Nothing are the apex of this -where you can polish an extremely useful product. And because it’s physical, it’s even more beautiful. We tried to do this for Reachy compared to our first open source project, the SO 101. These are robot arms that are made to be extremely cheap so not very polished. For Reachy we wanted a beautiful user experience. The qualia that you feel when you’re in the presence of a beautiful hardware product. There should be a name for that.

Sarah: I heard someone call this “spielzeug” once — the satisfaction of the weight of something in your hand, the idea that some of the physical objects you encounter in the world are perfect for reasons you can’t explain. My Nothing headphones are crafted with a certain depth of care that feels lovely somehow. Sélim: Basically. Thom: Yeah. Sélim: We try to distil the moods that are currently happening, the zeitgeist or whatever you want to call it, into an experience. Sometimes that goes into hardware, sometimes software, sometimes both. It goes across product categories. Something that Thom mentioned before; the narrative control of hardware is just so satisfying. In software, you launch it on the market and hopefully the story lands. Sometimes it doesn’t. Sarah: In open source, there’s an OG book, the Cathedral and the Bazaar, about different approaches to software from top down to bottom up. And what I’m hearing from you is that hardware is the cathedral; a beautiful structure you can own, a controllable narrative. And that’s funny because the other thing you two have in common is more of a bazaar approach versus, say, Apple. Nothing has radical transparency. You could argue Hugging Face have have owned the word “open” as the central platform for open source models. If the cost of hardware is coming down and more open source models can be integrated into products like Reachy, is hardware becoming more of a bazaar? Thom: Yes, it’s really the occasion to reinvent how we’ve made hardware. Traditionally think of hardware was the world of IP, closed systems, full control. And that’s one of the reasons it didn’t reach full potential. In the past, you could buy a lot of robots who typically had 15 behaviors that were pre programmed. You explore and then you’re like, okay, that’s all. Sélim: That’s pretty boring. Thom: I’m more excited about Reachy being open like iPhone. It arrives, and there are maybe a couple of apps on it but also a community building an entire app store of crazy behaviours. As the community grows, the hardware grows in being more and more useful. Sélim: The other side of this is the topic of craft. If we start to commoditize hardware creation, you dip into what software was ten years ago and peaks at now which is you throw everything onto the market and what wins is the product that understands what matters, that polishes the experience. I think this going to be important for hardware as well. Because no one likes gadgets. If you want to build something that has meaning, hardware is still very hard. Sarah: On fads, when we look at consumer robotics, what do you think in the next five years is going to break through? Assistance? Entertainment? Thom: I’m bullish on entertainment. We often see robots through the ens of industrial robots. I don’t find this very exciting. If we do this event again, in a year, it’d be cool to have robots walking around being playful and fun. I’m betting on entertainment and education. But obviously a lot of the field feels more strongly about retail as a use case. Sélim: If you walk around Shenzen, you see humanoid robots walking around, or robo dogs that for sure have an entertainent value. The question is; how long is it something you want to interact with? Right now, it feels like more of a gadget if you don’t connect with it on an emotional level. For instance, as in education. Education can take many forms, especially for younger kids. We used to have the word edutainment. Investors hated it; you couldn’t make any money there unless you were Duolingo. But that’s where I think embodiment can have value. Sarah: In Hardware 2024, Reggie James interviews a bunch of hardware founders and builders from Teenage Enginering to companies like Humane to friend.com and Rabbit which make the book feel like a snapshot of a scene at a time. Is this just the first wave of a next gen? Why now? Thom: AI opened this thing, right? I felt like the hardware was already pretty good but the software that was operating the hardware was frustratingly static. AI is this open ended thing where you can ask it anything and do anything. When you put that into a physical structure, it’s crazy. Hardware plus the physical implementation of AI is also a great way to learn and teach about the field. If I explain to my kids what AI does and we vibe code a website, it’s cool. But it’s really cool if I can vibe code the behaviour of a robot. Sélim: The underlying software that drives hardware is now so much more dynamic, adaptable, and that makes it suited to finally interact with the world we have. Because the world is not static. It’s ever changing. That’s why this Cambrian explosion, right? Because it’s this non -deterministic adaptive software that, given the right sensors, is able to make sense of what it sees, hears and feels. On one side, it makes it more valuable and exciting to build. But on the other side, we have to bring up China. They just know how to manufacture stuff. It’s systemic. The advantage they have, if you walk around there in Shenzhen or also Xi’, an, where actually a lot of stuff gets produced, is it’s brutally competitive. People that want to build the best product because they want to have the biggest market and that odrives the entire industry, it drives down prices, it creates innovation. Sarah: I just read Dan Wang’s Breakneck on modern China. The whole first chapter is about process knowledge in hardware, the idea of dense communities of folks that have manufactured for a long time. There’s a depth of community knowledge Every factory owner is an engineer. If you can’t solve a technical problem, your cousin probably can. What does that mean for Europe? Are we ever going to be able to reindustrialize? Thom: Yeah, that’s something I brought back from Shenzhen — how much knowledge we’ve lost. We travelled there with super simple proofs of concept because that’s the only way we could build them in Europe. They were just laughing — “we can mold anything”. So we actually redesigned our robot this summer to make it more complex so that we can build it, because we ship it in kits and the less pieces you have, the better it is. I think we should try to bring back this knowledge. But there’s also what you’re saying; the network. When you go to Shenzhen, in a day, you have a thousand people that have your WeChat and they’re ready to collaborate with you. Sélim: It’s systemic. The way the systems are built up in China for hardware manufacturing creates these value flywheels where people want to capture the market with the best product and the best price. If you try to replicate that in Europe, it’s difficult because people here don’t want to compete that hard anymore. So what happens is the open market. Why try to do it yourself when you can buy for very cheap ten times the quality you could make? Thom: This doesn’t mean we shouldn’t try. How could we bring some of this knowledge back? Sarah: Agreed. How do you both think about hardware onboarding? Sélim: I really love building products that tap into existing behavior. When it comes to onboarding, try to understand what is the user familiar with; what do they identify with when they buy the brand. Reduce time to value. As a product, you’re demanding attention and value from user with the delayed promise of giving them value later on. How do you make them invest into the product before them dropping out because they’re bored or annoyed? You don’t battle the time but the attention of the user. Thom: One thing we think for each mini is the first hour experience. I want the first hour to be great. Some, like Lego, have pushed this to the extreme. The onboarding is the pleasure. But for robotics it should be fun to open the box. It should be fun to build the thing. Then you should have first apps, things that give you a bit of reward and you have a whole ecosystem being built and installed. People should not have to wait one week to start getting value. The clear takeaway is you cannot force anyone to do anything. We see this in our larger scale community. You can’t actively push a community in one direction. I say that we nudge people. Sarah: How do your communities help evolve the product? Sélim: For Nothing, community is integral to how the company was built. We tap into their creativity. We built products that directly create that creative flywheel for the community. We ask for designs, the designs are debated then we literally manufacture it and sell it. For us, community is part inspiration, part reality check. But it also drives the underlying system. I can’t say too much but soon we’re going to dip even further into that creative power because AI really allows you to give tools to people. All this increases the value of the product. Thom: Same for us. Community is super important. We even built hardware to create community because open source AI was so broad but within that robotics had very little community. The reason is that all the robots are too expensive. So our cheap one can grow a new open source robotics community by providing tools. Sélim: And the tools build retention. Thom: That’s the next thing we’re paranoid about. Sélim: Yeah, how do you build these habits? How do you make them understand that if they keep doing xyz, they get the reward, so make them come back. Sarah: On that point around retention, when we think about hardware categories, we’ve had smart glasses, AI pins, wearables. What are form factors that in five years will be dominant and not throwaway toys? Sélim: I don’t have the answer. Cool on Friend and other wearables for trying. The difficulty is to make the user care enough because just wearing it then you get a download of your day is boring. You’re going to do this once or twice and then you’re bored of it. How can you give non-intrusive value throughout the day? What is the emotion that you connect to throughout the day without being too intrusive? I think the difficulty with the wearables category. Thom: There’s a chicken and egg problem of social acceptance of these things. You have your weird Google Glass; everyone is looking at you and you stop. It was a smart move to partner with Ray Bans so the Meta glasses make you stand out less. This will probably change, you know, in the coming year and people get used to having various devices for good or bad. Sélim: This goes back to habits. Glasses, I love them. It’s a cool product, especially with Neural Band. Sick. The question; how many will they sell and how big is the market? Sarah: But we said the same about phones. Sélim: Yeah, that’s right. It feels like it’s a version of the future that is possible. Sarah: There’s a lot of founders in the room. We’re living in a time of AI accelerationism and public ARR charts and yet hardware takes time. Thom: It’s tough. Maybe you need more money to build it. But as with anything if you’re building a harder startup, you have to be really passionate about it. I think it’s way more tough. That’s why we’re tackling it with a lot of care and trying to start small.

Sélim: Yeah, experiments with cheaper robots. But my founder answer, really, is tune it out. There’s so much noise in the market and it’s nonsense. As a first time founder, the question your friends ask you most is “how big is your team” as if this gives you legitimacy. How about how much my customers pay me? These are the metrics founders should care about. Not Linkedin nonsense. Tune it out. See trends, see what drives society, both are important for software and hardware. Sarah: What is overhyped right now in hardware? Thom: All these new wearables. The smartphone is still a great piece you can play on. Sélim: I think so as well. The smartphone will stay. From a Nothing perspective, the smartphone is like an entry point. We made it clear in our previous communication that Nothing is not a smartphone company but a consumer electronics company that tries to build the next platform. What’s overhyped? Probably wearables but I love them. Sarah: What’s underhyped? Sélim: Bringing a lot of sensors together and throwing intelligence at them and then kind of trying to figure out what they can do. Thom: Communities. Sarah: If AI and hardware lives up to its promise, what does that mean to you? Let’s go back to Utopia. Let’s finish on Utopia. Thom: I really like this idea of pure creativity; someone has a great idea and then it’s very simple to build a company around it. With coding, people can quickly made a website which used to a be a huge endeavour. Robotics and hardware can evolve like that. Sélim: I guess we all have beautiful places in mind. But it’s also that we will have more time to be creative. Less drudgery during our day. I think Utopia feels like we’re going to be more creative, more free, more human again in a way. Sarah: That is a beautiful note to end on. |